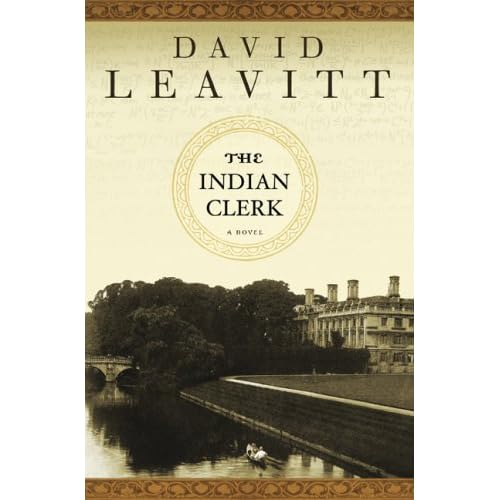

The best historical novels -- Gone with the Wind, for example -- make you live history. Immersed in characters, some fictitious, some real, the reader re-imagines the past, filtered through the author's vivid imagination. I was therefore intrigued to hear that David Leavitt was going to write a historical novel about the celebrated relationship between the mathematicians G. H. Hardy and Srinivasa Ramanujan. His new book, The Indian Clerk is not quite a historical novel; at least it is not a good historical novel. It is perhaps accurately described as novelized history. It gives a good account of the four years that Ramanujan spent at Cambridge with Hardy -- an account far more entertaining and fun, than say, a scholarly biography of Ramanujan would be. It is a tepid novel, but a good read.

The best historical novels -- Gone with the Wind, for example -- make you live history. Immersed in characters, some fictitious, some real, the reader re-imagines the past, filtered through the author's vivid imagination. I was therefore intrigued to hear that David Leavitt was going to write a historical novel about the celebrated relationship between the mathematicians G. H. Hardy and Srinivasa Ramanujan. His new book, The Indian Clerk is not quite a historical novel; at least it is not a good historical novel. It is perhaps accurately described as novelized history. It gives a good account of the four years that Ramanujan spent at Cambridge with Hardy -- an account far more entertaining and fun, than say, a scholarly biography of Ramanujan would be. It is a tepid novel, but a good read.The story -- of genius found, and lost -- hardly needs re-telling. In January 1913, G. H. Hardy, already famous, and at the height of his powers, received a letter from a man called Ramanujan, a clerk living in Madras, asking for suppport. With the letter are several pages full of mathematics. Hardy, to his credit, a genuine mathematician in those pages. He, and J. E. Littlewood, his collaborator, arranged to have Ramanujan come over to Cambridge. Ramanujan had little formal education, having dropped out of college because losing his scholarship, his obsessive interest in mathematics leading him to neglect all his other subjects. The mathematics he knew was almost all self-taught -- and his lack of knowledge combined with his genius meant that he rediscovered independently many important theorems that others had already discovered before. The collaboration between Hardy and Ramanujan, with Hardy doing his best to channel Ramanujan's genius, was enormously productive although Ramanujan never really adapted to England. Distressed with the food, hampered by the cold, worried about his family back in India -- he left immediately after the war was over. Within the next year, he was dead. He was only 32.

Leavitt tells this story from different perspectives, often in confusing succession. Mostly it is through Hardy, who collaborated closely with Ramanujan but never really took the effort of making him feel at home. Even here, Leavitt switches disconcertingly between telling the story in the third person (with access to Hardy's innermost thoughts) and in the first (as "the lecture Hardy never gave"). We also get the perspective of some other characters: Alice Neville (the wife of the Cambridge Fellow Eric Neville, who, in the book's most overwrought portion, thinks she's in love with Ramanujan), Hardy's sister Gertrude, and G E. Littlewood.

The central theme, the weave that holds these narratives together is the strange effect the arrival of Ramanujan had on these individuals. Leavitt has certainly done a prodigious amount of research and it is a testament to his skill as a writer that he is able to novelize incidents and facts that he has culled from various sources. He is successful in giving a portrait of G. H. Hardy, richly imagining his innermost thoughts. But, and somewhat puzzling, Leavitt leaves Ramanujan alone, and does not even try giving us Ramanujan's version of events. He remains a strange figure, inscrutable, unknown, mysterious. Perhaps that is our duty to genius: novelists may choose to analyze them from the outside, but imagining their inner life is off-limits.

I may perhaps be guilty of wanting Leavitt to write a novel he had no intention of writing. But The Indian Clerk, with its the recycling of events, both true and fictitious, is fun too. What it isn't is transcendent.